Tier-2 and tier-3 cities in India now rank among the fastest-growing markets for mobile data, digital payments and streaming platforms.

Yet, India’s data-centre capacity remains overwhelmingly concentrated in tier-1 hubs of Mumbai, Chennai, Delhi-NCR, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Pune and Kolkata. The imbalance is increasingly visible in everyday digital experiences.

Streaming viewership climbed 14% year-on-year to 547.3 million users in 2024, driven by a 21% surge in ad-supported video platforms.

These services remain especially popular in tier-2 and tier-3 cities, where users increasingly prefer free content.

As of March, India had roughly 969 million internet subscribers, of whom 408 million lived in rural areas—a demographic that overlaps with the catchment zones of emerging edge markets.

Sify Infinit Spaces Limited (SISL) noted in its DHRP filings that “while colocation and hyperscale data centres have expanded significantly, their presence is predominantly limited to the top 10 cities.”

“This concentration has resulted in suboptimal digital experiences in tier 2 and tier 3 cities. To address this disparity, edge data centres are being deployed.”

This uneven distribution of infrastructure has created a structural challenge: India generates nearly 20% of the world’s data but holds only about 1% of global data centre capacity.

With most infrastructure locked into metros, vast regions depend on long-distance transmission.

Enter Edge Data Centres

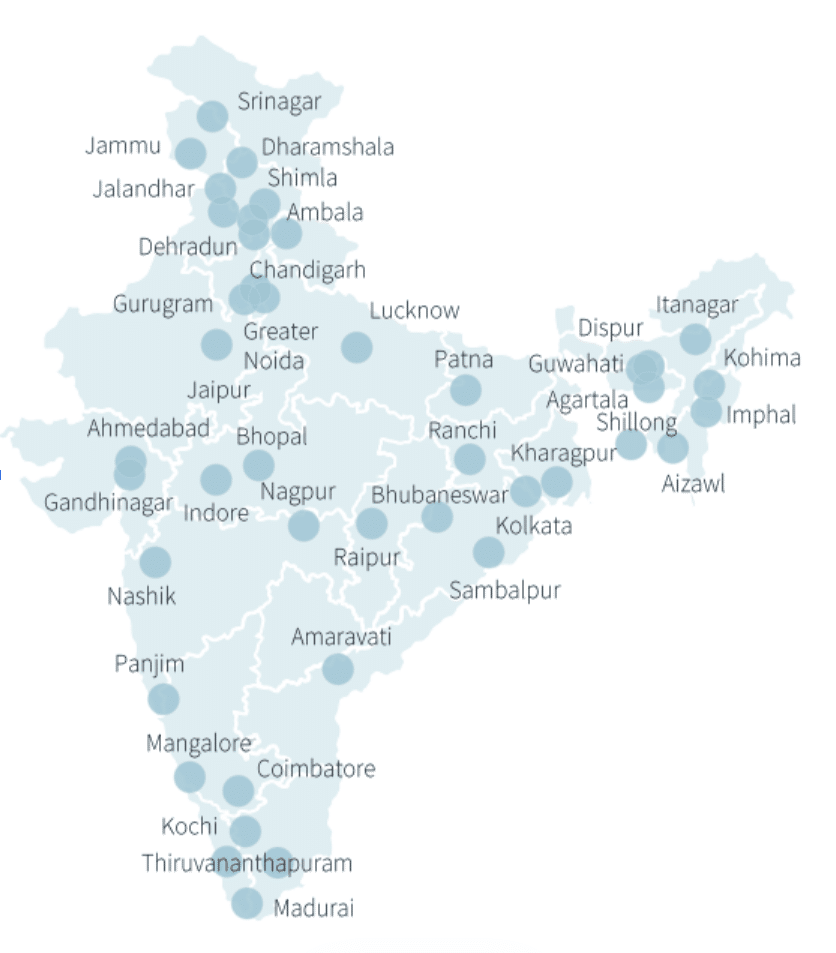

This imbalance has led to a surge in edge data centres — facilities placed closer to demand centres for large user clusters in Jaipur, Chandigarh, Ahmedabad, Kochi, Visakhapatnam, Lucknow, Patna, and Bhubaneswar.

While hyperscaler data centres handle compute-intensive, globally orchestrated workloads on a massive scale, edge data centres handle latency-sensitive, bandwidth-intensive workloads that often require data localisation.

“In India, latency drops significantly when workloads are processed closer to the end user at the edge data centre location in micro cities,” said Vipul Kumar, VP, edge and network at CtrlS Datacenters, in an interaction with AIM.

“Instead of traffic travelling to distant hyperscale regions like Delhi, Mumbai or Chennai, which adds multiple network hops and increases delay, local edge infrastructure keeps compute within the region,” he added.

This improvement is critical for various real-time workloads — fintech authentication, high-frequency trading, OTT streaming, autonomous logistics, and others.

The Rapid Expansion of India’s Edge Ecosystem

Operators are already repositioning to serve these markets. SISL is advancing edge projects in Lucknow and Chandigarh. CtrlS Datacenters is expanding a distributed network as well.

Anil Nama, CIO at CtrlS, told AIM, “CtrlS has already set up edge facilities in Patna and Lucknow and plans to add over 20 new facilities across tier-2/tier-3 cities of India over the next few years.”

Nxtra by Airtel operates 120 edge data centres across 66 locations.

RailTel, a government PSU, has begun deploying over a hundred small data centres at railway premises in partnership with Techno Electric & Engineering Company.

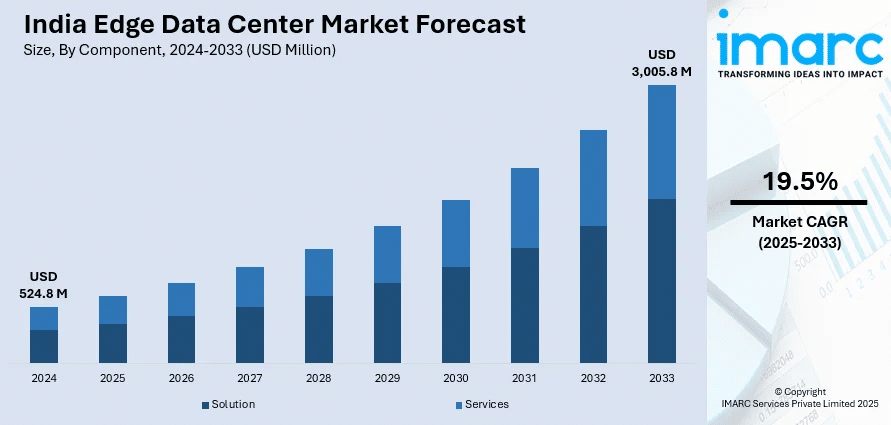

While hyperscaler and colocation capacity in India stands at around 1,200 MW, a JLL report stated that the country’s edge computing capacity is 80-100 MW and is expected to reach up to 180 MW in 2028.

As edge infrastructure grows, the performance gap between metros and non-metros narrows — but the broader shift is still unfolding.

Why Edge Data Centres Are Getting AI Capabilities

The shift extends beyond entertainment or basic internet use cases.

Growing adoption of apps like ChatGPT, along with government-backed AI programmes focused on Indic languages and sector-specific digital services, is pushing compute demand into smaller cities.

Many tier-2 and tier-3 cities already run edge centres built for content delivery and redundancy. Increasingly, they are being considered for high-density AI facilities, where latency becomes a decisive performance factor.

Edge data centre sites in India. Source: JLL

Kumar also pointed out how the differentiation between hyperscaler and edge data centres will not remain static.

Even as hyperscale data centres handle AI training, Kumar added that a significant part of the AI stack, including inference, real-time analytics, and localised AI processing, is already well-suited to edge data centres.

“The future isn’t edge versus hyperscale—it’s edge working in tandem with hyperscalers, creating a distributed cloud fabric that is faster, more resilient, and closer to where digital experiences happen,” said Kumar.

Companies like CtrlS are establishing edge data centre facilities with higher power densities, robust cooling architecture and other technologies that allow them to support GPU-based workloads.

Amit Agrawal, CEO of Techno Digital, told AIM, “India is not a very big country, but it is a sizable country where east to west coverage, or north to south coverage can take anywhere between 30 milliseconds to 45 milliseconds.”

And in the worst case scenario, if there is a delay of 45–50 milliseconds, AI will lose its relevance, he added

“Our [CtrlS] edge facilities are designed as CapEx-light, modular deployments, typically beginning with 50 to 100 racks—strategically positioned near India’s national fibre backbone availability,” said Kumar, stating how this provides ‘immediate’ low latency workloads — while keeping the architecture flexible to scale with AI requirements.

This is also where physical constraints in tier-1 cities begin to influence location strategy. A typical 10 MW data centre may require around 10 acres of developable land. India will need nearly 45 to 50 million square feet of new data centre real estate to support AI-era workloads — a scale that metros would struggle to accommodate.

Water requirements add further complexity. An AI-oriented 1 MW facility can consume about 25.5 million litres annually. Cities like Delhi, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad already face significant groundwater stress.

Agrawal noted that until recently, data centres were built primarily to meet hyperscaler requirements and remained concentrated in cities such as Mumbai and Chennai.

That logic, he said, has reversed. Data centres will now follow power availability rather than expecting power to be drawn to them, and future sites will be determined primarily by where reliable, scalable energy can be secured.

“Everybody wants to come to Mumbai. But today, the city’s peak power requirement is about 3 GW, and we are already talking about the Thane–Belapur Road coming up with nearly 1 GW of total data-centre capacity,” said Agrawal.

He noted the scale of the challenge such growth would create. “Just imagine a 15-kilometre stretch consuming one-third of the power of the entire Mumbai city. Are we ready for that? We are not.”

“Data centres will go farther from the cities wherever there is availability of power,” added Agrawal.

Nama reinforces economic logic. “Tier-2 and tier-3 cities are rapidly emerging as high-value data centre locations. Their significantly lower land and operational costs free up capital for cutting-edge infrastructure and phased hyperscale expansion,” he said.

Even within a tier-1 city, moving away from premium clusters such as Powai dramatically alters the cost equation.

SISL states a five-acre site for a 50 MW facility in Powai is priced at around ₹533 crore, whereas a comparable site in Panvel falls to roughly ₹41 crore.

This differential underscores how much more favourable the economics become as operators look beyond core metro zones and into emerging markets.

Cities like Visakhapatnam illustrate the convergence of these factors — coastal connectivity, favourable state policy, and growing operator interest — already visible in Google’s large-scale hyperscale data centre investment announcement.

Recently, Karnataka’s IT minister Priyank Kharge, also stated that the state will push for data centre establishments across the state’s coastal region, particularly in Mangaluru, which is also promising a growing IT ecosystem.

Kharge said the state is already working with the Department of Energy on a plan to earmark dedicated green energy for AI and data centres. “We will come up with a blueprint by the next budget session,” he noted.

How State Policies Are Accelerating the Shift

The transition beyond tier-1 cities is also being reinforced by state governments.

Tamil Nadu’s Data Centre Policy explicitly encourages investments beyond Chennai, promoting Coimbatore, Madurai, Tiruchirappalli, and Hosur as viable alternatives.

The policy provides 100% stamp-duty exemption in non-metro districts, 50% land-cost subsidies, and access to pre-developed IT parks across eight tier-2 locations with integrated water, sewage, fibre, and power readiness. It also ensures robust power provisioning through dual-grid supply and expedited substation augmentation.

Andhra Pradesh has taken an equally assertive approach. What makes the state’s push notable is that it lacks a conventional tier-1 metropolitan anchor, yet it is pursuing an unusually ambitious data centre strategy.

Its Data Centre Policy 4.0 (2024–29) is explicit in courting AI-enabled facilities and aims to add several hundred megawatts — potentially up to a gigawatt — of new capacity.

Investors receive 100% stamp-duty exemption, capital subsidies or SGST reimbursement, and relaxed building, zoning, and infrastructure norms.

However, until a facility is established, expansion to tier-2 and tier-3 hubs brings multiple challenges. “Each new city requires establishing relationships with local electricity providers, navigating municipal regulations, and building operational frameworks, all of which are time-intensive but essential activities,” said Kumar.

He also stated that selecting the location is critical. While many real estate players own land parcels, only a select few possess the right-sized land at strategic locations.

“Once established in a city, having navigated land acquisition, local regulations, and utility relationships, and having an operational presence on the ground, we can scale capacity considerably quicker than greenfield entrants starting from scratch,” said Kumar.

The post India’s Data Centre Expansion Is Decentralising appeared first on Analytics India Magazine.